What Are Payment Rails

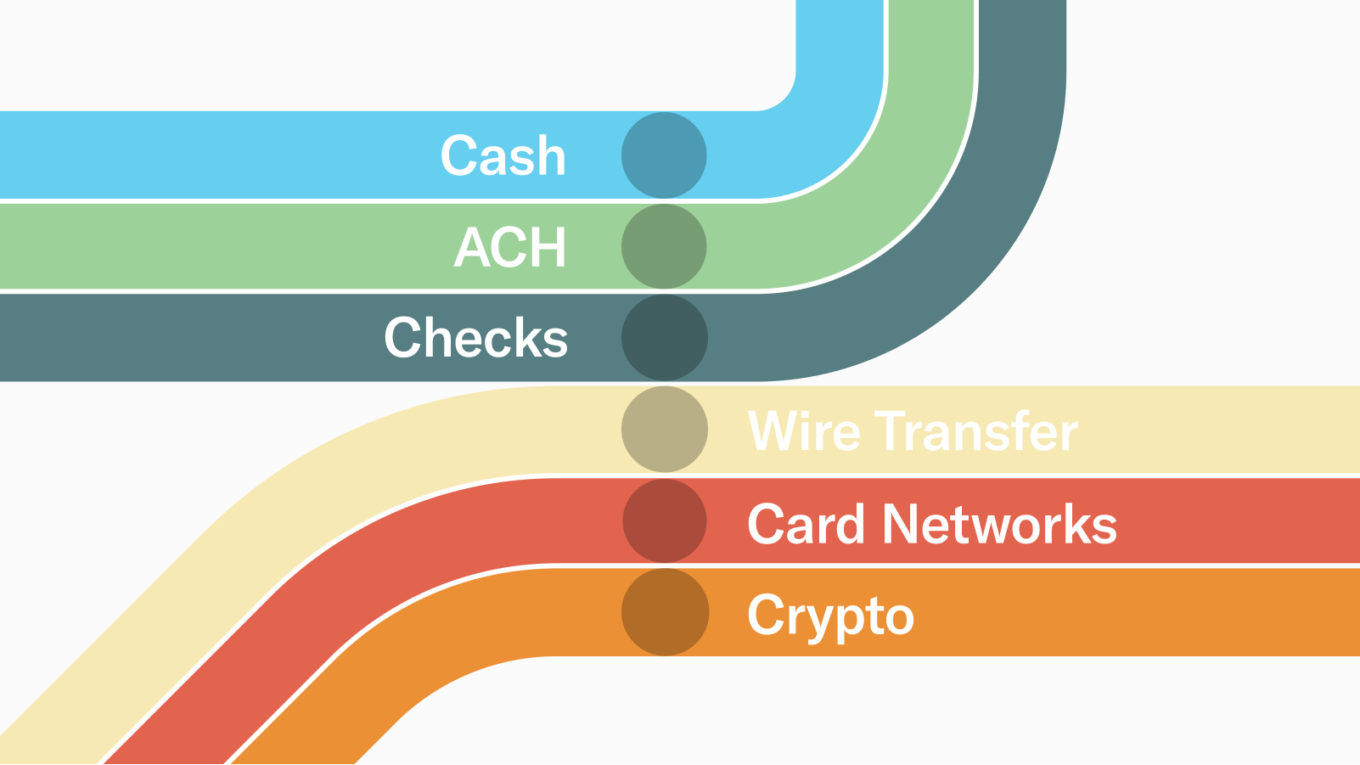

Over the past century, the number of payment rails has diversified due to new communication technologies, the increase in the number of transactions made per person per day, and the fact that most purchases are not in physical cash. From 2010 to 2020, for example, cash’s share of US transactions fell from over 40% to less than 25% (the post-COVID norm is likely to be far lower).

The most common of these payment rails in the US are ACH (“Automated Clearing House”), Fedwire, CHIPs (“Clearing House Interbank Payment System”), Credit Cards, PayPal, and peer-to-peer payment services like Venmo. These rails have different requirements, merits, and demerits.

Wires can only be used between (and thus through) banks and are only available during non-holiday weekdays. During business hours, transactions are not reversible, and cannot be used to request funds (so it doesn’t work for credit card payments, invoices, etc.), and have high sending fees (e.g. Chase pays <$0.15 per wire, but charges $25–45 per outgoing wire), receiving fees ($15 to receive), and additional fees for non-USD wire, failed wires, confirmations, etc. These fees make it particularly impractical for small sums to be transferred but are inexpensive for large transactions (e.g., individuals can wire up to $100,000.00). CHIPS, which is only available to 47 member banks, is the cheapest wire service and, therefore, the default choice for banks. However, the funds aren’t available to the recipient until the next day. Fedwire settles in real-time but is more expensive. Both solutions require a bank account. International wires typically take two to three days.

ACH is cheaper than wires; most banks allow customers to make ACH-based transfers for $0 or, at most, $5 and enable automatic ACH bill-pay for free. For the most part, businesses can make ACH payments to vendors or employees for less than 1% per transaction. Unlike wires, ACH is reversible and can be used to credit or debit accounts (hence automatically paying your wireless bills). However, ACH is much slower than wires — from one to three days. This is because ACH payments don’t “clear” until the end of the day, at which point a bank aggregates everything it must send to another bank (i.e., all ACHs) and sends it in one sum via Fedwire. The next day, the Fed sends the funds to the receiving bank, which must then deposit into the recipient account, which can take another day. This produces several challenges beyond just one to two and a half days where neither sender nor receiver has the funds. For example, ACH transactions can only be transmitted during business hours, and there’s no confirmation of a successful transaction — only an error. And that error takes several days to correct as the recipient bank doesn’t notice the failure until the second day. Its report isn’t processed till the end of that day, with the original sender receiving the failure notice the following day (at which point the three-day process starts again). However, ACH is considered much more secure and fraud-proof than any other mainstream payment rail. While wires can be made to non-US banks, ACH is domestic only.

Credit cards are another key payment rail. They involve swiping a physical card (or entering credit card information), after which a credit card machine or remote server captures account information and digitally sends it to the merchant’s bank, which then submits it to the customer’s credit card provider, which either grants or denies the transaction. This process takes one to three days and typically costs merchants 1.5–3.5% of the transaction. To pay off credit cards, customers typically make an ACH payment. Credit card payments work in most markets globally. Like ACH, but unlike wires, credit card payments are reversible.

Finally, there are the digital payment networks such as PayPal, Square, and the Cash App. Individual accounts are primarily funded via ACH or credit card, at which point the platforms then serve as a centralized/single bank used by all accounts. As a result, all transfers between users of the same payment platform are effectively just reassignments of money held by the platform itself. Given this, payments are instantaneous and when money is sent between friends and family, these platforms typically charge no fees. But when a business is paid, 1.5–3% transaction fees to the business are common. And if a user wants to move their on-platform money to their bank account, they must typically pay 1% (up to $10) for it to arrive same-day, or otherwise wait two to three days (during which the platform collects interest). There is no direct way to send cash from one digital payment network to another. In addition, many are US only.

The various US payment rails trade security, fees, and speed. No one is perfect, but their competition is more important than their technical attributes. There are multiple wire rails, credit card networks, digital payment processors, and platforms. Each of these competes based on its advantages and drawbacks, and even within one category, there are variable fees. Amex, for example, charges far more than Visa, but it offers consumers more lucrative points and perks, and to merchants, higher-income clientele. And if a user decides they don’t want a credit card or a merchant declines to take Amex, they have multiple alternatives available. Users can also make free payments if they’re willing to lend their money to a given network for two to three days.